Early Monotheism

One of the more consequential developments in the history of human

religion was the rise of monotheism, or belief in and worship of only

one god, rather than many. Monotheism has its origins in the Near

East during the early Iron Age. Drawing on a variety of sources,

the first monotheisms moved away from worship of a variety of

anthropomorphic deities in the direction of the worship of one

transcendent and all powerful creator God. Monotheism in general

tended to be more focused on individual ethics and personal faith than

the more communal and ritually focused paganism which preceded it.

Despite the claims of the monotheistic faiths that belief in one

god had represented the original religion of all humans, its seems that

monotheism actually developed gradually over a period of many centuries

and at first had much in common with ancient pagan worship.

Monotheism gained popularity in the ancient Near East only very

slowly, and coexisted and competed with polytheistic paganism for many

centuries before finally becoming dominant. Below are the most

important varieties of monotheism.

Aten Worship in

Egypt

The earliest true monotheism was promulgated in

Egypt during the thirteenth century BCE by the eccentric Pharaoh Akhenaten (Amenhotep IV). For

reasons which are still not entirely clear, but possibly as a means of

wresting power away from the wealthy and influential priesthood of the

god Amun, Akhenaten attempted to force Egypt to worship Aten, a sun god represented by the

image of the solar disc. In so doing, the Pharaoh adopted the

name Akhenaten ("Helper of Aten") and insisted not merely on the

supremacy of Aten, but on his status as the only real god.

He used violence to enforce his religious vision and to suppress

the worship of the more established Egyptian gods. It is perhaps

unsurprising then, that his religious reforms ended in failure

when his resentful subjects reverted to the old ways after his death.

Still, Akhenaten's promotion of the worship of only one,

non-anthropomorphic god counts as the first clear historical example of

monotheism, and may well have influenced subsequent versions of

monotheism even after it was stillborn in Egypt.

Zoroastrianism

One of the first

monotheistic religions, Zoroastrianism, had its origins in Persia

(Iran) beginning around the seventh century, BCE. Tradition

holds that this faith was founded by the Persian prophet Zoroaster, who called his people to abandon their

old pagan ways and to worship one particular and supreme deity, Ahura Mazda. Zoroastrianism is sometimes termed

a dualistic religion rather than a monotheistic one because it posited

the existence of a divine antagonist for Ahura Mazda called Ahriman. According to Zoroastrian doctrine,

these two supernatural beings were locked in a cosmic struggle for

supremacy, with Ahura Mazda as the champion of truth, light, and

goodness and Ahriman as the incarnation of deceit, darkness, and evil.

Believers were called by early Zoroastrian texts to live lives of

honesty and devotion to Ahura Mazda. Zoroastrianism thus focused

on the morality of the individual believer and promised a reward of an

afterlife in Paradise for the faithful and a corresponding punishment

in Hell for the wicked. Despite its doctrines involving two

divine beings, Zoroastrianism's focus on worship of Ahura Mazda alone

makes it a monotheistic faith, and one which would have a substantial

influence on the other monotheisms of the region.

Judaism

The religion

developed by the Israelites (the ancient ancestors of the Jewish

people) during the early Iron Age is often given credit for being the

first pure monotheistic religion in human history. Israelite

religion called for worship of a deity named Yahweh and focused on a system of sacrifices

conducted in the great Temple in the Israelites' capital city of

Jerusalem. Early Judaism also mandated a strict set of ethical

and ritual behaviors which helped set the Israelites apart from other

national groups in the ancient Near East and which were set down in the

scriptures of the Hebrew Bible some time during the first millennium,

BCE.

Another defining characteristic of early Judaism was

its strict insistence on the worship of Yahweh alone, accompanied by a

rigid prohibition against the use of any visual representations of God.

Despite these traits, most scholars believe that Israelite

monotheism developed only very gradually, and may have initially been a

form of monolatry,

acknowledging the existence of other gods, even as it urged the worship

of Yahweh alone. After centuries this focus on the cult of Yahweh

probably evolved into a genuine monotheism which held that only one

divine being really existed. Early Judaism seems to have lacked

any firm belief in an afterlife and was focused on a system of temple

sacrifices not dissimilar to those mandated by pagan religions of the

region. It was only after close Israelite contact with

Zoroastrianism following the Israelites' return from the Babylonian

exile in the sixth century BCE that Judaism seems to have developed its

more familiar modern doctrines of a diabolical adversary for God

and belief in an afterlife in Heaven or Hell for human beings.

Even into the modern era, Judaism has remained a national

religion for the Jewish people specifically, rather than a faith

seeking to spread among all people.

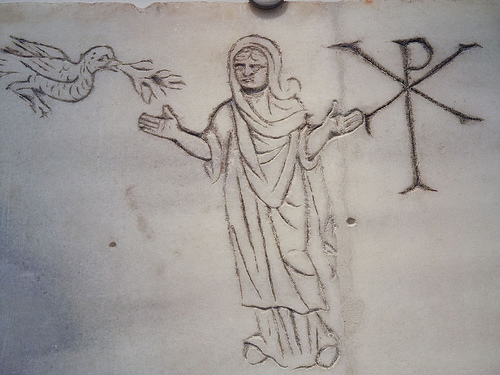

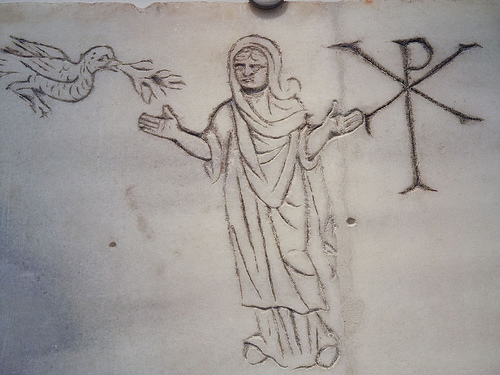

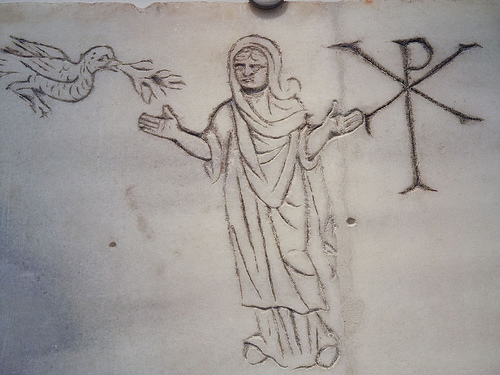

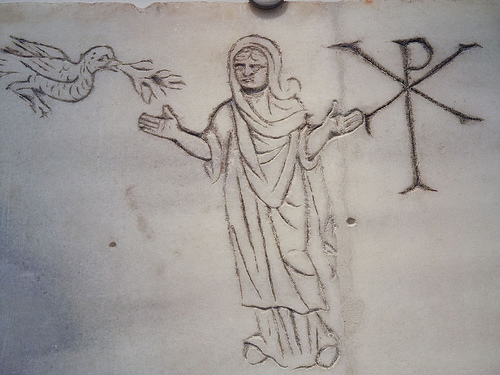

Christianity

During the first

century CE in Palestine a religion that became known as Christianity

started to develop as an offshoot of Judaism. This new

interpretation of an older faith centered around a Jewish itinerant

preacher named Jesus of Nazareth, who announced the imminent arrival of

the kingdom of God and called all believers to repent their sins.

Jesus' followers apparently believed that he was the Messiah, the long-promised king

from the lapsed royal line of David, sent to deliver the Jews to

independence once more. Indeed, the title attributed to Jesus, Christ, was a Greek rendering of the Hebrew word

for Messiah. Fearing that Jesus would become the focal point of a

Jewish rebellion against their rule in Palestine, Roman authorities

executed Jesus by crucifixion around the year 30 CE. According to

early Christian believers, however, Jesus supposedly rose from his

grave after three days and commissioned his disciples to spread the

good news (the gospel) to the world. Belief in Jesus' resurrection was to form a

cornerstone of the Christian faith.

While it would be

impossible to conceive of a Christianity without the figure of Jesus,

Christian doctrine owed an enormous debt to the preaching of Paul of Tarsus, a Hellenized Jew who had been a zealous

persecutor of Jesus' followers before his conversion to the faith.

Paul's writings held that Jesus' death had represented an

atonement for the sins of all people, and through faith in his divine

authority and resurrection, believers would have their sins forgiven by

God and receive the gift of eternal life. Paul also held that

Jesus' sacrifice meant that believers were saved through faith in

Christ rather than adherence to the detailed Jewish law expounded in

the Hebrew Bible, an innovation which made early Christianity much more

attractive to a non-Jewish audience.

Despite Paul's efforts to define this new religion

in clear terms, early Christianity remained an exceedingly diverse

movement which saw some sects such as the Ebionites calling for rigid observance of Jewish

religious law while others like the Marcionites denied any link to the Jewish religion

and its God at all. The conversion of the Roman Emperor Constantine to Christianity during the early fourth

century set the stage for the conversion of the Empire as a whole over

the next several centuries. It also prompted a clear definition

of Christianity as a faith distinct from Judaism which held that Jesus

had been God incarnate. The fourth century also saw the approval

of certain earlier Christian writings such as the letters of Paul and

other Church leaders as divinely inspired Scripture. These

documents came to be known as the "New Testament," and were appended to the so-called "Old Testament" of the Hebrew Bible, which was still

revered by most early Christians.

Islam

The second great

religious offshoot of Jewish monotheism came in the form Islam during

the early seventh century CE. It was founded by a minor Arabian

merchant named Muhammad who claimed to have heard a divine voice

urging him to "recite in the name of the Lord" while wandering in

prayer outside the city of Mecca. Over the course of the next two

decades, Muhammad claimed to receive regular messages from the God

worshiped by both the Jews and Christians, called "Allah" in Arabic. Initially, Muhammad's

message was unpopular, especially with the Quraysh tribe which controlled Mecca, a site of

pilgrimage for pagan Arabs. Eventually, however, Muhammad's

message of the equality of all human beings before God and his staunch

proclamation of monotheism began to win over convents. By the

time of his death in 632, the Arabian peninsula was well on its way to

conversion to Islam, an Arab term meaning both "peace" and "submission"

(to the will of God). During the generation following his death,

Muhammad's prophecies were written down and codified into a book of

scripture called the Qu'ran. Muslim doctrine held that both the

Jewish and Christian scriptures had been corrupted over time, but that

the Qu'ran represented the pure and unadulterated words of God Himself.

Among other

things, the Qu'ran called Muslims to uphold the Five

Pillars of Islam: 1) Witness

2) Prayer five times daily in the direction of the holy city of Mecca

3) alms-giving, 4) fasting during the month of Ramadan, and 5) a

pilgrimage at least once in a lifetime to Mecca if at all possible.

Additionally, Muslims were enjoined to be honest and merciful, to

have compassion for the oppressed and needy, and to lead ethical lives.

Islam also posited a clearly defined afterlife which promised an

eternal reward for the faithful servants of God and everlasting

punishment for those who did not acknowledge his authority. The

text of the Qu'ran, and well as a later set of writings known as the Hadith became the basis for Sharia, or Islamic law. In Islamic

civilization, there was no separation of religious and political

authority, and the head of state was called Caliph ("commander of the faithful"), an office

which combined political rulership with an obligation to nurture and

spread Islam. Indeed, Islam did spread quite rapidly in the

century after Muhammad's death, as Arab armies conquered Persia, North

Africa and parts of Asia Minor. Conversion to Islam was

encouraged but generally not coerced, although adherents of other

faiths had to pay special taxes and accept certain restrictions not

imposed on Muslim residents of the this empire.

Thus, by the dawn

of the Middle Ages, Christianity and Islam were the dominant religions

of the Western world, while Zoroastrianism and Judaism still could

claim substantial numbers of believers. The older varieties of

paganism, however, were on their way to becoming a thing of the past.

References

The following books are the sources of the information on this page,

and will provide more detail on these topics.

David G. Bradley. A Guide to

the World's Religions. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice

Hall, Inc., 1963.

Bernard Lewis. The Middle East:

A Brief History of the Last 2,000 Years. New York:

Scribner, 1995.

Susan Niditch. Ancient

Israelite Religion. Oxford: Oxford University Press,

1997.

Herschel Shanks, ed. Ancient Israel: From Abraham to the Roman

Destruction of the Temple. Washington, DC: Prentice Hall,

1999.

John Dominic Crossan. The Birth

of Christianity. New York: Harper Collins, 1998.

John McManners, ed. The Oxford Illustrated History of

Christianity. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001.

Bart Ehrman. The Lost

Christianities: The Battles for Scripture and the Faiths We Never Knew.

Oxford: Oxford

University Press, 2003.

Karen Armstrong. Islam: A Short History. New

York: Random House, 2000.

Robert Wright. The Evolution of God. New

York: Little, Brown and Company, 2009.

All content copyright D. Campbell, 2010.

Excerpt photo

source: www.flickr.com/photos/mharrsch